LIMITI DI EQUILIBRIO

Giovanni Anselmo, Agostino Bonalumi, Alexander Calder, Sérgio de Camargo, César, Gianni Colombo, Walter Leblanc, François Morellet, Giuseppe Penone, Angelo Savelli, Nobuo Sekine, Jesùs-Rafael Soto.

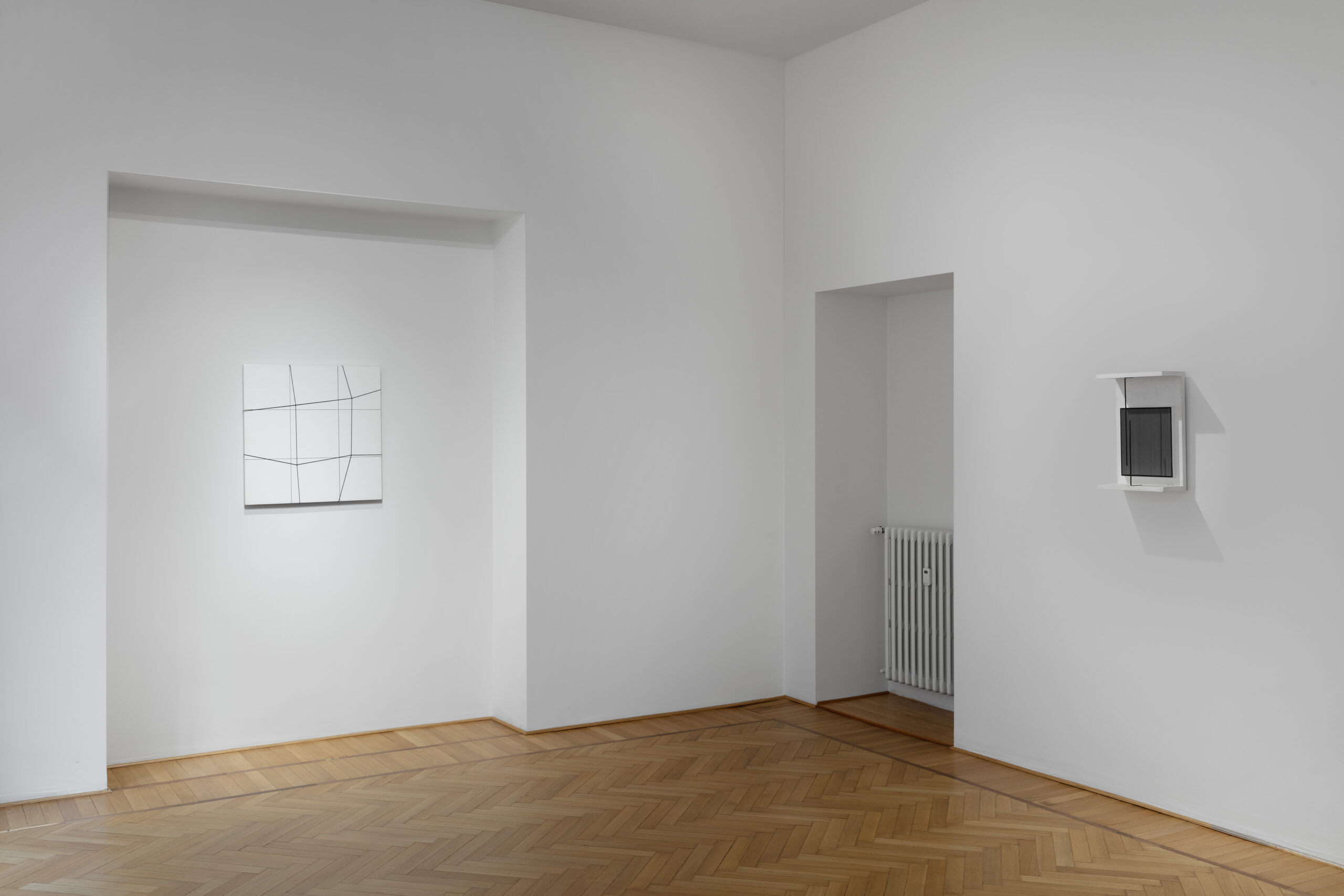

Limiti di equilibrio is an invitation to go on a journey of discovery, starting from the point of view of each of the twelve exhibited artists, and continuing with our personal perception of balance.

In each selected work, it is the individual artist, with his own vision, who becomes the creator of the ideal boundary, the limit, above or below which the stability of the elements can be compromised. In each painting and sculpture on display, every artist achieves, in his particular way, the culminating point where visible and invisible, inside and outside, form and substance, light and shadow are balanced until they become an indissoluble whole.

The continuous research of a balance can be read as an attempt to give their own sense to the nonsense, to capture the instant of beauty in order to stop the never ending becoming of things, seeking for a momentary order within the disorder of the existence.

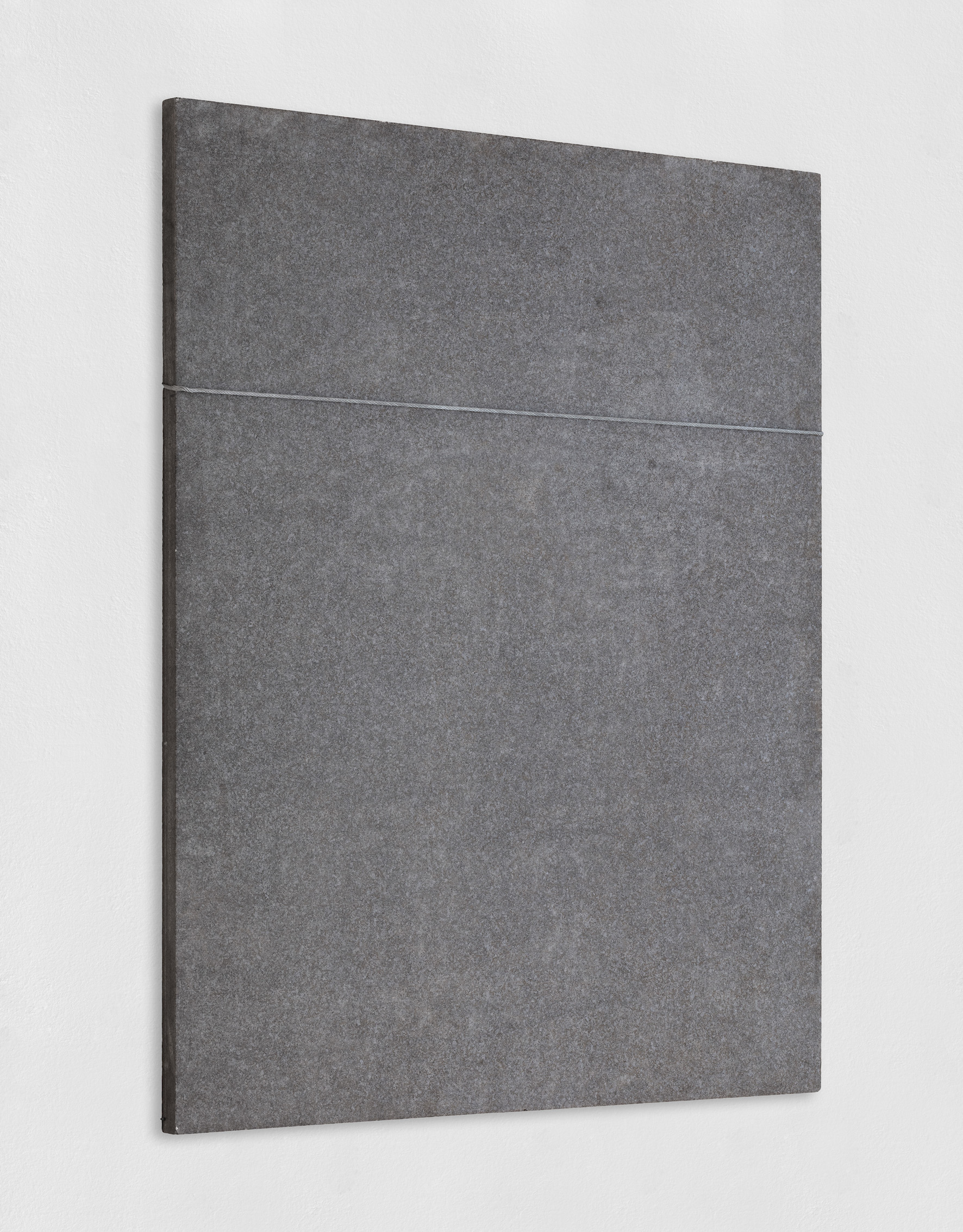

“A lot of my output was sculpture. While I was working on the Venice Biennale piece, I wanted something that was more two-dimensional, back to the wall, and that’s how I started this series. (Nothing of Phases).” Nobuo Sekine, in Mousse Magazine, 2019.

Nobuo Sekine explores the interdependence and balance between the natural quality of form and its continuous change in time and space. Through the use of simple materials, both organic and industrial, the artist aims to reveal the reality beyond appearance, reconsidering the relationship between man and space, matter and reality. An object, a work is never different from the space it occupies, nor does it coincide with it. Both object and space contribute to creating its meaning.

“I have often done works that start from ideas that are in each occasion time in a broad sense, or the infinite, or the invisible, or the whole, perhaps simply because I am a terrestrial and I am limited in time, in space, in the particular”. G. Anselmo (1972, alla nascita del “Particolare”), in “Giovanni Anselmo. Entrare nell’opera”, exh. cat. of the National Academy of San Luca, 2019.

Through his works, Giovanni Anselmo attempts to reveal the inhate energy of the matter. The concreteness of the material together with the invisible energy manifested by the object, ‘physicalize’ the force of an action produced by matter. Each work stems from the manifestation in space and time of the suppressed and emergent forces that the elements produce as they encounter one another.

The artist creates the conditions for initiating a situation that contains balance and tension: as in the work “Il colore mentre solleva la pietra, la pietra mentre solleva il colore”, the position of the stone alludes to a potential loss of weight, but it is thanks to the continuous action of the force of gravity that the work holds itself up and with its weight relentlessly tightens the slipknot.

Agostino Bonalumi, Rosso, 1966, extroflexed canvas and vinyl tempera

In the Agostino Bonalumi‘s extroflexions and painting-environmental works, the tension of the canvas creates a balance between shapes and perceptive space, making the surfaces vibrate due to the different incidence of light and different viewpoints. Harmonious conceptual and physical movements run from one boundary to another, from one form-space to another, stimulating the tactile experience.

As Bonalumi wrote: “In the persistence of the extroflexion, the technique, the means, the instruments by which the surface is pushed outwards or retracted inwards change, giving rise to the thought of a space behind the work“. ¹

Sérgio de Camargo‘s reliefs and monochrome sculptures are elegant explorations of solids and voids. Using structures with volume and position variations, the artist delves into the expressive and dramatic potential of light and shadow, that inhabite the work, going beyond the geometric space. The light occupies the space between the cylinders, creating an interrelation among the elements and giving to the relief a sense of vitality, rhythm and harmony. A perfect convergence and balance between painting and sculpture.

“Cutting an apple to eat it, he sliced off nearly half and then made another cut at a different angle to take a piece out. The two planes made a simple relationship between light and shadow.” Guy Brett, “Sergio Camargo”, in Sergio Camargo: Liber Albus (São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2015), 246.

The perceptual balance that characterizes François Morellet‘s work is the result of continuous work on opposites. Strict objectivity clashes with elements of randomness, creating bizarre systems that develop autonomously.

The work on show, entitled 3 Trames de grillage 0° -4° +4°, was executed in 1974 and created by using weaves or grids, one of the forms that characterizes his oeuvre. The title explains its rationale: three metal grids, each angled differently (0° -4° +4°) in relation to the vertical in opposite directions, that overlap evenly a black painted wooden panel. The sculptural nature of the wire, protruding slightly from the support, interacts through the optical effects of the textures.

The elementary ambiguity of the perception of the geometric shapes created by optical contrast on the uniformly and neutrally white background, makes us perceive them as representations of solids in projection, therefore in an initial misleading drawing nature. The limit of sensory balance is created as a personal interpretation by modifying the tensions. Gianni Colombo wrote: “In other words, it can also be defined as an experimental construction with which to survey the optical and psychic behavior of its user, who will bring in the variables due to his physical and psychic reactions, coming to self-determine, in part, the image he perceives“. ²

Here again, the limits of balance are revealed subjectively, nullifying the objectivity of the subject.

“The skin like the eye, is a boundary element, the end point capable of dividing and separating us from what surrounds us, the final point capable of physically enveloping enormous expanses…It is the point that allows me, still and after all, to recognize myself.”

Giuseppe Penone, Penone Archive.

On the right Giuseppe Penone, Unghiate, 1989, torn paper and plaster on frame

In the Giuseppe Penone’s work, the investigation on the nail concept takes part of the analysis of the relationship between the human body and the surrounding nature, of the boundary between the inner self and the outer world, encouraging the dialogue between the two parts. The claw mark is a small time capsule containing traces of an action. Evidence of the search for a connection, of the cancellation of limits and the interpenetration between skin and matter.

For César, balance, from a physical point of view, is to be understood as the maintenance of stillness. The transformation process of compressed materials reaches the limit of balance between the reacting forces, creating Compression.

In Angelo Savelli‘s work, the use of white color, space and form contribute to the dialectic around the balance between outside and inside, finite and infinite, temporal and timeless dimensions.

White is absolute, everything begins and ends in it. Space is formal, it expands without definition. Light, with its natural and inevitable incidence, balances the internal tensions, helping the form to achieve a perfect balance between structure and strength.

“The universe is real but you can’t see it. You have to imagine it. Once you imagine it, you can be realistic about reproducing it.” Alexander Calder, in The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists, New York, 1962.

Alexander Calder‘s balance is dynamic and calibrated, capable of going beyond material supports and generating movement from instability. It is always a fragile, unstable balance, whose limits are contained in both stasis and movement.

“Today, the notion that there is mankind on one side and the world on the other has been superseded. We are not observers but constituent parts of a reality that we know to be teeming with living forces, many of them invisible.” Jesús-Rafael Soto, in Jean Clay, “Les Pénétrables de Soto”, Robho, n°3, Paris, 1968.

In Jesús-Rafael Soto‘s work, there is a direct communication between the work and the brain that bypasses the eye. The protagonist of Kinetic art builds a balance by adding the viewer to the work itself. The position of the observer changes the characteristics of the vision but not the substance and the limits of the balance it carries.

For Walter Leblanc, painting is the result of tension and balance between strict rules and creative freedom. Rhythm, order and light combine with our own view creating a balance between the extremes, such as reason and sensitivity, reflection and intuition. As art historian Jan Hoet writes wrote: “His work constantly appeals to the flexibility of the limits of the frame, and the limitations are modified to become possibilities”. ³

[1] A. Bonalumi, Evoluzione dialettica in Bonalumi, Evoluzione continua tra pittura e ambiente, exh. cat. curated by di L.M. Barbero, Galleria Niccoli, Parma, 2000.

[2] Flaminio Gualdoni in Gianni Colombo. Opere 1959-1979, exh. cat. Gianni Colombo. Opere 1959-1979, Studio Gariboldi, Milan, 2010.

[3] Jan Hoet, Ghent, 2001